Wolf-Ekkehard Lönnig (2003):

Biston betularia: Wo befinden sich 99,9% der Birkenspanner nach allen bisherigen Daten tagsüber bzw. wo befinden sie sich tagsüber nicht?

(Biston betularia: Where do 99.9% of the peppered moths rest by day

according to all the known data - or where

do they not rest?)

In 25 years we have only found two betularia on the

tree trunks or walls adjacent to our traps

(one on an appropriate background and one not), and none elsewhere.

Sir Cyril Clarke

Of about 100 lepidopterists present at a monthly meeting of the Finnish

Lepidopterological Society,

nobody

had ever found the

species in day-rest on tree trunks. Similarly, lepidopterists in Germany have wondered

why the species is hardly ever found on trunks,

if these constitute the main resting place of the species...

Kauri Mikkola

If the relative fitness of the morphs of the peppered moth does depend on their crypsis,

the resting position is crucially important to the estimation of fitness differences between the morphs.

Michael E. N. Majerus

This seems reasonable.

Bruce S. Grant

(Kommentar zu dem soeben zitierten Punkt von Majerus.)

So much stuff has been published by British scientists since Kettlewell,

and none is very conclusive...(und zuvor:)

Kettlewell's colleagues didn't want to shoot him down because they loved the idea.

It was an example of Darwinism.

Ted Sargent

(Zitiert nach Hooper.)

The worst use of theory is to make men insensible to fact.

Lord Acton

(John Emerich Edward Dalberg Acton)

Inhalt

Nachtrag 5. September 2007: Siehe Kommentar von Jonathan Wells zu neueren Behauptungen zu Biston betularia unter Exhuming the Peppered Mummy

(31. Oktober 2007:) Kernpunkt von Wells' Kritik: "In the seven years during which Majerus was peering out his window, far more than 135 peppered moths visited his back yard, but (as previous research showed) he couldn’t see most of them because they were resting high in the upper branches of his trees. Those he could see from the ground represented only a tiny fraction of the total.

In his 1954 classic, How To Lie With Statistics, Darrell Huff devoted his first chapter to sampling bias. He wrote: “The test of the random sample is this: Does every name or thing in the whole group have an equal chance to be in the sample? Obviously, the vast majority of peppered moths were NOT in Majerus’s sample because they were resting where he couldn’t see them. Yet the very question he set out to answer was where they rest! If Huff were writing his book today, he might well use Majerus’s statistic as an egregious example of sampling bias."

2. Einleitung: Meine Rezension von Kutscheras Evolutionsbiologie und Herrn E.F.’s Einwände dazu

3. Eine grundsätzliche Anmerkung zum Thema Korrekturen

4. Dokumentation zur Frage, wo sich die Birkenspanner tagsüber aufhalten bzw. nicht aufhalten

b) Weiter Michael E. N. Majerus

c) Die Zusammenfassung der Biston-Problematik nach Jonathan Wells

6. Die Verneinung dieser Sachkritik

7. Die Fehlinterpretation zweier Tabellen aus Michael E. N. Majerus durch Kenneth R. Miller

9. (a) Wells’ Kommentar zu Millers Deutung der Tabellen

(b) Die Einwände von N. Matzke, B. Grant, K. Padian und A. D. Gishlick

10. Tamzeks (Matzkes) Extrapolation von Baumstämmen auf Baumkronen ist fragwürdig

English Summary

An extensive documentation of facts is presented below showing that the peppered moth (Biston betularia) does not normally rest in exposed positions on tree trunks (except in perhaps less than 0.1% of the cases). 99.9% of the moths rest in unexposed positions mostly high up in the canopies. Thus, the biological and evolutionary textbooks have, in fact, to be revised on the issue of the peppered moth.

The questionable interpretations of two tables of M. E. N. Majerus (1998) on the resting positions of B. betularia by several leading proponents of the synthetic theory (K. R. Miller 2002, N. Matzke 2002, B. Grant 2002, K. Padian and A. D. Gishlick 2003) have also been documented in detail and corrections have been suggested on the basis of the facts so far known.

Although almost all of my comments are written in German, the English speaking reader will also profit from the documentation because most of the quotations describing the relevant facts and data are in English.

Emphasis: Nearly all cases of emphasis (bold, italics, underlined) in the quotations have been added (except species names which are usually written in italics in most languages). This may facilitate easy reading, focussing on the main points of the text.

Eine ausführliche Untersuchung der Frage, wo sich Biston betularia in aller Regel tagsüber aufhält, bzw. nicht aufhält hat die Aussage von Sir Cyril Clarke und zuvor von Kauri Mikkola voll bestätigt: Die Birkenspanner rasten – von möglicherweise weniger als 0,1% aller Exemplare abgesehen – tagsüber nicht auf Baumstämmen, oder genauer, sie befinden sich nicht "in exposed positions on tree trunks". Mit diesem Forschungsergebnis fällt der Hauptpunkt heutiger Lehrbuchdarstellungen, der Selektion der unterschiedlichen morphs durch Vögel in Abhängigkeit von der Tarnung der Birkenspanner auf Baumstämmen.

Anders lautende Behauptungen beruhen (1.) auf der eklatanten Fehlinterpretation zweier Tabellen von Majerus (1998), und/oder (2.) auf einer Verdrehung des Streitpunktes (es geht nicht darum, ob Biston betularia überhaupt "in exposed positions on tree trunks" gefunden wird, sondern um die Frage nach den Frequenzen und den Relationen dieser Frequenzen zueinander), oder (3.) auf einer gezielten Ausblendung der entscheidenden wissenschaftlichen Tatsachen zur Frage, wo sich Biston tagsüber aufhält, bzw. tagsüber nicht befindet. Der Leser achte bei der Beurteilung der verschiedenen Einwände von Kritikern einmal ganz genau auf diesen Punkt (zumindest in einem Fall wurde die entscheidende Aussage von Sir Cyril Clarke nach Hooper sogar ganz präzis aus einem längeren Zitat herausgeschnitten).

Weiter können die Befunde zur selektionstheoretischen Situation von "exposed positions on tree trunks" auch nicht einfach auf die Baumkronen ("Blätterdach"), genauer "underneath, or on the side of, narrow branches in the canopy" übertragen werden. Oben hatte ich Majerus (1998, p. 123) mit dem Satz zitiert: "If the relative fitness of the morphs of the peppered moth does depend on their crypsis, the resting position is crucially important to the estimation of fitness differences between the morphs." (Siehe auch die Zustimmung von Grant, oben.) Die resting position wäre jedoch für die Selektionsfrage völlig uninteressant, wenn wir von den exposed positions auf Stämmen einfach auf die fitness differences between the morphs in den Baumkronen extrapolieren könnten. Wir könnten dann die Forschung zu dieser Frage ruhen lassen, und auch der weitere Hinweis von Majerus (p. 125), dass zur Beantwortung dieser Frage Beobachtungen an Birkenspannern an ihren natürlichen Rastplätzen dringend notwendig sind ("moths being taken from natural resting places

are urgently needed"), wäre überflüssig (biologische Details, die gegen die Extrapolation sprechen, siehe unten).Was nun das Thema Selektion überhaupt betrifft, so habe ich kürzlich auf eine Anfrage von Herrn Markus Rammerstorfer, Linz (Österreich), Folgendes geantwortet:

Selbstverständlich bestreite ich nicht jeden Einfluss der Luftverschmutzung auf die populationsgenetischen Veränderungen bei den Birkenspannern und vielen weiteren ähnlich gelagerten Fällen (siehe im Detail Lönnig 1993/2002

http://www.weloennig.de/AesV1.1.Indi.html) und - wie der Leser des letzteren Beitrags schnell erkennen kann - bestreite ich auch nicht grundsätzlich den Faktor Selektion:"Da solche schwarzen Varianten auch in den Wäldern Schottlands, in Nordkanada und in den Regenwäldern der Südinseln von Neuseeland nachgewiesen sind (vgl. z.B. Kahle 1984, und oben Lees und Creed sowie Parkin), ist das Auftreten schwarzer Formen nicht an Industriegebiete gebunden, - wahrscheinlich aber die Frage des Selektionswerts, woraus die Frequenz in den verschiedenen Populationen folgt."

Und weiter unten:

"Die zitierten Möglichkeiten und die Dominanzverhältnisse lassen folgende unterschiedlichen Hypothesen zu:" ...1. ... Die allgemein hohe Frequenz der gescheckten Varianten in nicht-industriellen Gebieten, abgesehen von 'peat bogs' und 'dark shady pines', wird vor allem durch den Selektionsvorteil (Scheckung als Schutzmuster) erklärt."

Als ich diesen Text schrieb, war mir jedoch der Hinweis von Sir Cyril Clarke und anderen Autoren noch nicht bewusst: "All we have observed is where moths do not spend the day. In 25 years we have found only two betularia on the tree trunks or walls adjacent to our traps (one on an appropriate background and one not), and none elsewhere" (Clarke et al. 1985). - Die Frage der Scheckung als Schutzmuster als Tarnung vor "Vogelfraß" muss also völlig neu durchdacht und untersucht werden. Wenn sich jedenfalls 99,9% aller Birkenspanner tagsüber nicht "in exposed positions on tree trunks" aufhalten, dann kann dieser bisher als entscheidend betrachtete Selektionsfaktor auch nicht mehr als sicher für die Melanismusfrage beim Birkenspanner angesehen werden und die üblichen Aussagen zu diesen Problemen in den Lehrbuchdarstellungen von Kutschera und vielen anderen sind unbewiesen.

Sollte aber dieser Faktor - im Gegensatz zu allen neueren Befunden – letztlich doch noch stringent nachgewiesen werden, oder vielleicht auch ein ganz anderer Selektionsfaktor oder deren mehrere, so werden selbstverständlich auch diese Ergebnisse akzeptiert.

Wenn hingegen die Selektionsfrage schließlich für alle entscheidenden Fragen negativ beantwortet werden sollte, dann wird ein ehrlicher Forscher auch mit diesem Ergebnis keine grundsätzlichen Schwierigkeiten haben. Tatsache ist, dass die genaue Antwort zur Selektionsfrage - trotz einiger guter Hinweise zugunsten selektionstheoretischer Erwägungen - zur Zeit noch weitgehend offen ist.

Ganz sicher ist jedoch die Bestätigung des Gesetzes der rekurrenten Variation

durch den 'Industriemelanismus' (vgl. zu dieser bedeutenden Frage noch einmal das Kapitel INDUSTRIEMELANISMUS http://www.weloennig.de/AesV1.1.Indi.html - siehe auch unten). Damit ist die Behauptung widerlegt, dass mit der Beschreibung der Biston-Mikroevolution auch ein wesentlicher Beitrag zur Beantwortung der Frage nach den Faktoren der Makroevolution überhaupt geleistet worden sei.Die systematische Bestätigung des Gesetzes der rekurrenten Variation durch das Phänomen des Industriemelanismus wird meines Wissens in sämtlichen Stellungnahmen zur Thematik durch Vertreter der Synthetischen Evolutionstheorie bisher (Juni 2003) völlig ausgeklammert. Der Hauptgrund ist wohl der, dass die in der biologischen Realität festgestellte und durch das mutationsgenetische Gesetz der rekurrenten Variation (+ Selektion + genetic drift/neutrale Mikroevolution + physiologische Faktoren/Modifikationen) erklärte begrenzte und zyklische Variation der Phänotypen beim Birkenspanner (und vielen weiteren Beispielen) der Idee der fortschreitenden Evolution widerspricht, die u.a. auch mit diesem Beispiel in Lehrbüchern vermittelt werden soll.

Das Biston-Beispiel war gewissermaßen ein "Juwel in der Krone der Synthetischen Evolutionstheorie" (S.E.), insbesondere in dem umfassenden Programm mit der Hauptzielsetzung "...die Planmäßigkeit auf jede Weise aus der Natur loszuwerden" (wie es Jakob von Uexküll treffend formuliert hat). Der Leser beurteile bitte anhand der hier aufgeführten Tatsachen und Argumente wieder selbst, ob und falls ja, inwieweit dieses Juwel seinen Glanz verloren hat oder sogar ganz aus der Krone des Neodarwinismus entfernt werden sollte.

Der besondere Stellenwert des Birkenspanner-Beispiels im Programm gegen die Planmäßigkeit in der Natur und die nun erkannte Fragwürdigkeit der Biston-Theorie aufgrund zahlreicher biologischer Tatsachen, erklärt auch das ungewöhnliche Ausmaß an ad-hominem-Kritik (Diffamierungskritik)

http://www.weloennig.de/Antwort_an_Kritiker.html seitens einiger Vertreter der Synthetischen Evolutionstheorie gegen diejenigen Biologen, die diese Problematik heute öffentlich diskutieren.Schließlich ein Wort zur hohen Redundanz der Aussagen in den folgenden Ausführungen: Das Phänomen ergibt sich zum Teil aus der Notwendigkeit der Dokumentation der im Prinzip durchweg einheitlichen Antworten zu unserem Thema sowohl von ein und demselben Autor als auch von mehreren unabhängig voneinander arbeitenden Forschern und Verfassern:"…peppered moths do not naturally rest in exposed positions on tree trunks…" "…peppered moths do not habitually rest in exposed positions on tree trunks…""…peppered moths generally rest in unexposed positions…" usw. usf..

(Anbemerkung: Fast alle Hervorhebungen im Schriftbild der obigen und folgenden Zitate sind von mir vorgenommen worden. - Emphasis in the quotations - bold, underlined, and nearly all italics by W.-E.L..)

2) Einleitung: Meine Rezension von Kutscheras Evolutionsbiologie und Herrn E.F.’s Einwände dazu

In meiner Rezension

http://www.weloennig.de/RezensionKutschera.html zum Thema Einige gravierende Fehlinformationen in Herrn U. Kutscheras Lehrbuch Evolutionsbiologie (Parey Buchverlag Berlin 2001) habe ich im Rahmen einer Diskussion nur einen einzigen, aber entscheidenden Punkt zur Problematik des Biston-Beispiels herausgegriffen (siehe unsere Thema, - aber die meisten anderen Punkte, darunter auch die grundsätzliche Frage nach der Bedeutung der Selektion, die ich – ganz im Gegensatz zu den Behauptungen einiger Kritiker – keineswegs ablehne [vgl. Lönnig: Industriemelanismus http://www.weloennig.de/AesV1.1.Indi.html] aus Zeitgründen hier nicht weiter ausgeführt). Im Zusammenhang mit Darwins Hinweis auf die Schwierigkeiten, die in Verbindung mit "false facts" entstehen, habe ich die Frage nach dem ‚Tagesrastplatz’ der Birkenspanner dann wie folgt behandelt:Tatsächlich bestehen die entscheidenden Punkte aus Kutscheras Lehrbuch zu diesem Thema (2001, pp. 184-186) aus solchen "falschen Tatsachen". Ich greife hier nur einmal die "falsche Tatsache" der Baumstämme als Tagesrastplatz der Nachtfalter heraus (man könnte mehrere weitere "falsche Tatsachen" allein aus diesem Abschnitt aus Kutscheras Lehrbuch herausarbeiten). Kutschera schreibt 2001, p. 184: "Die Nachtfalter sitzen am Tag bewegungslos auf Baumstämmen und fliegen nur während der Dunkelperiode umher (Abb. 9. 5). " (Pp. 184/185): "Natürliche Feinde der Nachtfalter sind die Vögel. Es wurde beobachtet, daß Singvögel selektiv jene am Tag unbeweglich an Stämmen sitzenden Falter fressen, die sie optisch wahrnehmen (sehen) können: Weiße Birkenspanner auf hellem Hintergrund (bzw. schwarze auf dunkler Rinde) können aufgrund ihrer Tarnfärbung von potentiellen Feinden kaum erkannt werden...In einem unverschmutzten Wald (helle Baumstämme) wurden 984 markierte Birkenspanner ausgesetzt..." usw., usf. ("Die dunkle Mutante hatte auf den weißen Birkenstämmen nur eine geringe Überlebenschance und wurde daher weitgehend eliminiert"; pp. 185/186).

Die Schwierigkeit mit solchen "false facts" liegt für den Leser darin, dass er sie auch bei großem Scharfsinn meist nicht ohne weiteres durchschauen kann. Denn wer kommt schon angesichts der oben zitierten Behauptungen Kutscheras und vieler weiterer Lehrbuchautoren auf die Idee, dass diese Falter normalerweise überhaupt nicht auf Baumstämmen "sitzen" weder tagsüber noch nachts? Wer kommt auf die Idee, dass die Nachtfalter statt dessen von Kettlewell und anderen Versuchsveranstaltern zumeist auf die Baumstämme gesetzt (oder tagsüber ganz in deren Nähe freigelassen) wurden oder sogar aufgeklebt worden sind (aber nicht von Kettlewell)? Wer kommt dabei auf den Gedanken, dass die Nachtfalter tagsüber fast ausnahmslos "in shaded areas under branches" in Ruhestellung verharren? ("It is now universally acknowledged that Cyril Clarke, who laconically observed that in twenty-five years he had seen exactly two Biston resting on tree trunks, was right after all: the normal daytime resting place of peppered moths is not on tree trunks but in shaded areas under branches, where colour differences would be muted" – J. Hooper: Of Moths and Men, 2002, pp. 265/266, kursiv von Hooper, bold von mir). Wohl kaum ein Leser wird jeden einzelnen der in einem naturwissenschaftlichen Lehrbuch als Tatsache aufgeführten Punkte in Frage stellen wollen! Und ein Student wird viel eher bereit sein, die als Tatsachen vermittelten Punkte "gläubig" anzunehmen!

Aber nach der schon als "kleine Sensation" zu bezeichnenden Buchbesprechung von Coyne in Nature 1998 zur Aufdeckung dieser "falschen Tatsachen" (Sargent et al., 1998; Majerus, 1998; Coyne, 1998) hätte ein Lehrbuchautor im Jahre 2001 das nun wirklich besser wissen können und meiner Auffassung nach sogar müssen!

Eingeleitet hatte ich die Diskussion dieses Kritikpunkts mit dem 1999 verfassten Zitat aus der Corsini-Enzyklopädie (formuliert in Anlehnung an die Ausführungen der Vertreter der Synthetischen Evolutionstheorie Coyne, Majerus und Sargent):

(a) The peppered moth normally doesn’t rest on tree trunks (where Kettlewell had directly placed them for documentation); (b) The moth usually choose their resting places during the night [genauer: dawn], not during the day (the latter being implied in the usual evolutionary textbook illustrations); (c) The return of the variegated form of the peppered moth occurred independently of the lichens "that supposedly played such an important role" (Coyne); and (d) Kettlewell’s behavioral experiments have not been replicated in later investigations. Additionally, there are important points to be added from the original papers, as (e) differences of vision between man and birds and (f) the pollution-independent decrease of melanic morphs.

Zu den von führenden Evolutionstheoretikern auf dem Gebiet erarbeiteten, sich über Jahrzehnte erstreckenden und auf genauen Studien an Zehntausenden von Biston-Individuen basierenden Einwänden zu verschiedenen Aspekten der Lehrbuchdarstellung des Birkenspanner-Beispiels gibt es eine umfangreiche Gegenkritik, und zwar ebenfalls von Vertretern der Synthetischen Evolutionstheorie. Dabei ist insbesondere die Zusammenfassung der Forschungsergebnisse durch Jonathan Wells die Zielscheibe der Angriffe. Obwohl ich mich nicht mit den über die Biologie hinausgehenden Motiven und Zielen von J. Wells und des Discovery Instituts identifizieren kann, erscheinen mir viele dieser Angriffe bedauerlicherweise mehr auf eine Diffamierung der Person abzuzielen, als auf eine Richtigstellung der biologischen Fragen (siehe die Details unten).

Herr E.F. antwortete zu meiner obigen Darstellung:

E.F.: Das kann ich nun überhaupt nicht nachvollziehen. Die genannten Einwände stammen, wenn ich das richtig sehe, aus Majerus, M.E.N. 1998. 'Melanism: Evolution in Action' Oxford University Press, Oxford. Coyne, J. A. 1998. 'Not black and white' Nature 396:35-36. Hooper, J. 2002 'Of Moths and Men. Intrigue, Tragedy and the Peppered Moth' Fourth Estate, London.

.....[Kommentar zu Popper]

Dass die gesamte Fragestellung sehr komplex ist, wurde in letzter Zeit im Zusammenhang mit Well's Buch 'Icons of Evolution' hinreichend dargestellt. Sehr instruktiv ist die Darstellung in http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/wells/

Dort finden Sie auch Links zu den OnLine erhältlichen Artikeln, beispielsweise zu der Arbeit von Coyne und Arbeiten von Grant

Grant, B.S. (1999) 'Fine Tuning the Peppered Moth Paradigm' Evolution 53 (3):980-984 (eine kritische Würdigung von Kettlewells Arbeiten auf der Basis des Buchs von Majerus und dessen Rezension durch Coyne)

Grant, B.S. (2002) 'Sour Grapes of Wrath (Rezension HOOPER: Of Moths and Men)' Science 297:940-941 (eine vernichtende Kritik des Buchs von Hooper)

W.-E.L.: Nach jahrelangen Erfahrungen mit "vernichtenden Kritiken" neodarwinistischer Autoren, die sich bei genauer Prüfung immer wieder als weitgehend unbegründet herausgestellt haben (und sich häufig – aber nicht immer – auf pure Polemik und/oder Ablenkungsversuche reduzierten), werde ich zunehmend kritisch bei solchen Empfehlungen, - allerdings nur, um diese um so genauer auf ihren faktischen Inhalt zu überprüfen.

Tatsächlich wird nun die Frage, wo sich der Birkenspanner tagsüber aufhält, in der "vernichtenden Kritik" von 2002 gar nicht erst gestellt und in der 1999er Arbeit insofern bestätigt, als Grant p. 4 feststellt: "In truth, we still don’t know the natural hiding places of the peppered moth." Würden sich die meisten Birkenspanner jedoch tagsüber – wie nach gängigen Lehrbuchdarstellungen zu erwarten – "in exposed positions on tree trunks" aufhalten, dann wüssten wir das längst, denn wir hätten dort schon Tausende von Exemplaren allein in den letzten fünfzig Jahren gefunden!

Weiter erstaunt mich, dass Herr E.F. in seinen Anmerkungen und Literaturempfehlungen vom 18. Dezember 2002 nicht auch die entscheidende Antwort von J. Wells vom 16. April 2002 mit dem Titel Moth-eaten Statistics: A Reply to Kenneth R. Miller aufgeführt hat (aber vielleicht kannte er diese nicht). Weiter schreibt Herr E.F.:

E.F.: Ich denke, dass in den Artikeln von Grant und dem Artikel von TalkOrigins auf die Kritiken, nicht nur von Wells, hinreichend eingegangen wurde.

3) Eine grundsätzliche Anmerkung zum Thema Korrekturen

W.-E.L.: Zum Thema Korrekturen im Zusammenhang mit unserer Thematik zunächst eine grundsätzliche Anmerkung: Sollte es sich nun schließlich doch noch herausstellen, dass die von den führenden Evolutionstheoretikern auf diesem Gebiet (Bishop, Brakefield, Cherfas, Clarke, Cooke, Creed, Dornan, Grant, Green, Howlett, Jones, Liebert, Majerus, Mani, Mikkola, Owen, Sargent, Wynne und anderen) selbst erhobenen Einwände zu verschiedenen Aspekten der Lehrbuchdarstellung des Birkenspanner-Beispiels unrichtig sind, d.h. also der Wahrheit in der Tat nicht entsprechen würden, so bedarf es keiner weiteren Diskussion, dass auch die Korrektur der Korrektur akzeptiert wird. (Einer der führenden Vertreter der Synthetischen Evolutionstheorie hat mich einmal – nachdem er zunehmend in Erklärungsschwierigkeiten in einer mündlichen Diskussion mit mir gekommen war – als "Wahrheitsfanatiker" tituliert. Ich weiß nicht, ob ich diese Kategorisierung als Kritik oder Kompliment in diesem Zusammenhang auffassen soll, oder vielleicht beides. Wer mich kennt, weiß, dass es mir jedenfalls um ein möglichst genaues und wahres Verständnis der biologischen Tatsachen und Zusammenhänge geht.)

Was nun meine oben wiedergegebene Kritik betrifft, so kann der Leser ohne Mühe erkennen, dass ich mich nach der generellen Einleitung aus der Corsini-Enzyklopädie bei der Diskussion des Birkenspanners auf genau einen Punkt der Darstellung in Ulrich Kutscheras Lehrbuch konzentriert habe, nämlich auf die Frage: Wo befindet sich Biston betularia tagsüber bzw. tagsüber nicht? (Es sei noch einmal hervorgehoben, dass auch die Selektionsfrage ein besonderes Kapitel erfordern würde und dass ich gegen eine selektionistische Erklärung keine grundsätzlichen Bedenken habe.)

Auf unseren hier diskutierten Punkt aber kommt Herr E.F. bedauerlicherweise nur im weiteren Sinne durch seine Hinweise auf Literaturangaben ‘zu sprechen’ – ohne die Frage jedoch selbst zu diskutieren. (Und, wie schon oben erwähnt, führt er die entscheidende Antwort von J. Wells dabei nicht mit auf.)

Aber andere Verfasser lassen diesen Punkt völlig weg oder schneiden ihn sogar ganz gezielt aus (siehe Hinweis oben).

4) Dokumentation zur Frage, wo sich die Birkenspanner tagsüber aufhalten bzw. nicht aufhalten

a) Sir Cyril Clarke

Die Antwort auf die Frage, wo sich die Birkenspanner in aller Regel tagsüber befinden, bzw. nicht befinden, hatte ich in der Rezension mit Sir Cyril Clarke nach Hooper (2002, pp. 265/266) wie folgt gegeben:

"It is now universally acknowledged that Cyril Clarke, who laconically observed that in twenty-five years he had seen exactly two Biston resting on tree trunks, was right after all: the normal daytime resting place of peppered moths is not on tree trunks but in shaded areas under branches, where colour differences would be muted" – J. Hooper: Of Moths and Men, 2002, pp. 265/266, kursiv von Hooper.

Zur Frage nach der Richtigkeit dieser Aussage sollte man wissen, welche Kompetenz Sir Cyril Clarke zu dieser Frage mitbringt. Judith Hooper hat diesen Punkt sehr schön veranschaulicht, indem sie 2002, p. 272, berichtet:

[Grant] decided to try to repeat Bernard’s experiment with Biston cognataria [genauer Biston betularia cognataria], the American version, but he couldn’t catch enough. Colleagues told him that the man to see was Cyril Clarke, who ‘trapped more moth in one summer than anyone else together’, and soon he was ensconced at Clarke’s estate on the Wirral Peninsula near North Wales…

Und eine Seite weiter (p. 273):

From 1959 until the late 1990s, the Clarkes never missed a summer of daily trapping and ended up with data spanning more than three decades, more than 18,000 specimens in all, that documented in full the historic demise of the melanic peppered moth."

Ein weiterer Kenner der Materie, Michael E.N. Majerus (Department of Genetics, University of Cambridge) zitiert (1998, p. 121) ebenfalls Cyril Clarke nach Hinweis, dass die Anzahl der publizierten Berichte von Birkenspannern, die auf Baumstämmen gefunden wurden, zu vernachlässigen ist ("However, the number of published records of peppered moths being found on tree trunks is negligible")

, wie folgt:This is emphasized in an admission by Sir Cyril Clarke (Clarke et al. 1985): ‘All we have observed is where moths do not spend the day. In 25 years we have found only two betularia on the tree trunks or walls adjacent to our traps (one on an appropriate background and one not), and none elsewhere’.

Und das Zitat im Zusammenhang aus der Originalarbeit von Sir Cyril Clarke et al. (1985, p.197, nach der Diskussion verschiedener Fragen zum Thema Lichens and smoke):

But the problem is that we do not know the resting sites of the moth during day-time. Mikkola (1984) states that they settle on the upper branches of trees and he shows a photograph of a typica moth in this situation against the camouflage of a white lichen. We do not believe that this type of protection occurs in our area and all we have observed is where the moths do not spend the day. In 25 years we have only found two betularia on the tree trunks or walls adjacent to our traps (one on an appropriate background and one not), and none elsewhere.

(Italics by Clarke.) Sind diese klaren und eindeutigen Aussagen nun zutreffend oder unzutreffend, falsch oder völlig richtig?

Zur Beantwortung dieser Frage sollte sich der Leser auch völlig im Klaren darüber sein, dass weder Sir Cyril Clarke und seine Mitarbeiter G. S. Mani und G. Wynne, noch Michael E. N. Majerus, noch die im Folgenden zitierten Biologen, Kritiker der Evolutionstheorie sind und meines Wissens auch keinerlei Interesse daran haben, die ID-Theorie zu unterstützen (auch Hooper hat sich deutlich sowohl gegen den Kreationismus als auch gegen die ID-Theorie ausgesprochen). D.h., keiner der hier zitierten Evolutionstheoretiker hatte oder hat auch nur das geringste evolutionsbiologische (etwa grundsätzliche Ablehnung des Neodarwinismus zugunsten anderer Evolutionstheorien) oder sonstiges Interesse daran, die übliche Lehrbuchdarstellung in Frage zu stellen. Ganz im Gegenteil, die meisten dieser Biologen waren hochmotiviert, das Biston-Paradebeispiel der Synthetischen Evolutionstheorie mit umfangreichen Daten weiter abzusichern.

Zu dem einen Punkt, auf den ich mich in der Darstellung in Ulrich Kutscheras Lehrbuch konzentriert habe ("Wo befindet sich Biston betularia tagsüber bzw. tagsüber nicht?"), berichten alle Biologen, die über Biston selbst gearbeitet haben oder zumindest genau über den Birkenspanner informiert sind, in Übereinstimmung mit Sir Cyril Clarke und Mitarbeiter ("

All we have observed is where moths do not spend the day..." – vgl. auch Hooper: ".. the normal daytime resting place of peppered moths is not on tree trunks...") nun weiter Folgendes (und meines Wissens hat keiner dieser Biologen seine Aussage zurückgenommen):b) Weiter Michael E. N. Majerus

Zunächst einige weitere Aussagen von Majerus zur Frage, wo sich Biston tagsüber aufhält:

Majerus, 1998, p. 121, nach Hinweis auf die Arbeiten und Ergebnisse Bernard Kettlewells:

"…peppered moths do not naturally rest in exposed positions on tree trunks…"

Und die Aussage im Zusammenhang:

However, a number of workers have questioned the quantitative accuracy of these estimates, because peppered moths do not naturally rest in exposed positions on tree trunks (Mikkola 1979, 1984; Howlett and Majerus 1987; Liebert and Brakefield 1987).

Und Majerus noch einmal p. 121:

"…peppered moths do not habitually rest in exposed positions on tree trunks…"

Und diese Aussage wieder im Zusammenhang:

Data on the natural resting sites of the peppered moth are pitifully scarce, and this in itself suggests that peppered moths do not habitually rest in exposed positions on tree trunks. Many nocturnal moths do rest by day on tree trunks and searching trunks has long been a recognised method of collecting employed by lepidopterists. However, the number of published records of peppered moths being found on tree trunks is negligible. This is emphasized in an admission by Sir Cyril Clarke (Clarke et al. 1985): ‘All we have observed is where moths do not spend the day. In 25 years we have found only two betularia on the tree trunks or walls adjacent to our traps (one on an appropriate background and one not), and none elsewhere’.

Majerus, pp. 121/122:

"…

peppered moths generally rest in unexposed positions…""…These findings corroborate those from experiments to investigate the resting positions of captive male (Mikkola 1979, 1984) and female (Liebert and Brakefield 1987) peppered moths."

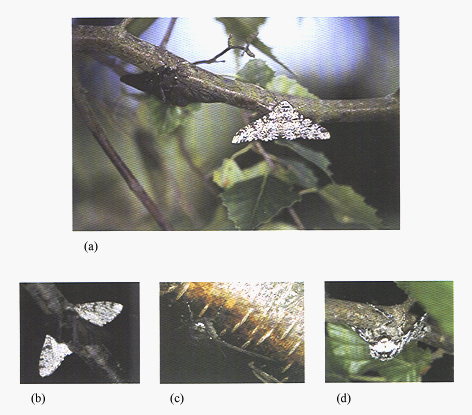

Auch diese Aussage im Zusammenhang:

The largest data set of the resting positions of wild pepper moths found in truly natural positions (i.e. not near moth traps or other light sources which may have attracted the moths) is of just 47 moths found over a period of 34 years (Howlett and Majerus 1987). Analysis of these results (Table 6.1) and an additional data set of the resting positions of moths found close to moth traps or street lights (Table 6.2), led Howlett and Majerus to conclude that peppered moths generally rest in unexposed positions, using three main types of site: (a) tree trunks, a few inches below a branch/trunk join so that the moth is in shadow; (b) the underside of branches (Plate 3a-c); and (c) foliate twigs (Plate 3d and Fig. 6.3). They also note that their data are bound to be biased towards the lower parts of trees, as these are most easily searched. These findings corroborate those from experiments to investigate the resting positions of captive male (Mikkola 1979, 1984) and female (Liebert and Brakefield 1987) peppered moths.

Majerus, p. 122:

"Mikkola...concluded that in nature this species probably rest on the underside of horizontal branches in the canopy…"

Die Aussage wieder im Zusammenhang:

Mikkola watched male moths taking up resting positions in large experimental cages containing section of trees, and concluded that in nature this species probably rest on the underside of horizontal branches in the canopy, where it may be less prone to bird predation, or may be exposed to different predators from those which habitually search tree trunks.

Majerus, p. 122:

"Liebert and Brakefield…obtained similar results. Most of the moths rested under, or on the side of, horizontal branchlets in the tree canopy…"

Die Aussage im Zusammenhang:

(Pp. 122/123) Liebert and Brakefield (1987) conducted similar experiments using females and obtained similar results. Most of the moths rested under, or on the side of, horizontal branchlets in the tree canopy, rather few are resting on non-horizontal branches, main branches, or trunks.

Anecdotal support for the proposition that peppered moths tend to inhabit woodland canopies, high above the ground, comes from the finding that moths (p. 123) traps set on the roof of Juniper Hall in Surrey, caught more than four times the number of peppered moths than similar traps set at ground level (Clare Dornan and Bryony Green personal communication).

Majerus, p. 123:

"…the view that peppered moths do not always, or even usually, rest in exposed positions on tree trunks is not original. Kettlewell (1958b) himself was aware [of this]..."

Bernard Kettlewell selbst (1958, nach Majerus):

"...I have on many occasions been able to watch the species taking up its normal resting position which is underneath the larger boughs of trees, less commonly on trunks."

Und der Zusammenhang:

It is worth noting that the view that peppered moths do not always, or even usually, rest in exposed positions on tree trunks is not original. Kettlewell (1958b) himself was aware that tree trunks were a less commonly used resting site than under branches, for he wrote:

whilst undertaking large-scale releases of both forms (f. typica and f. carbonaria) in the wild at early dawn, I have on many occasions been able to watch the species taking up its normal resting position which is underneath the larger boughs of trees, less commonly on trunks.

Und auch die Aussage von Bernard Kettlewell aus seiner Originalarbeit im Kontext. Er schreibt nach Aufführung einiger Daten für seine umstrittene background preference theory ("...moth are sensitive to the position they choose"*) 1958, p. 217:

Furthermore, whilst undertaking large-scale releases of both forms in the wild at early dawn, I have on many occasions been able to watch this species taking up its normal resting position which is beneath the larger boughs of trees, less commonly on the trunks. On the majority of occasions the moth, having flown on to a bough, stops fluttering and proceeds to walk a distance of a foot or more. Having selected a site which is nearly always the optimum one available in the immediate vicinity, it proceeds to turn a circle on its own axis in a series of jerks at the end of each one of which it clamps its wings and body down close to the bark. Finally it either moves to another area or takes up a permanent position.

(Bold und kursiv ebenfalls von mir.) Hier muss weiter berücksichtigt werden, dass diese Beobachtung von Kettlewell aus "Freisetzungsversuchen" "at early dawn" vom Boden eines geographischen Areals aus stammt, so dass die Formulierung "less commonly" noch eine Untertreibung der wirklichen Gegebenheiten sein dürfte. Tagsüber verhalten sich die Birkenspanner von ihrem natürlichen Verhalten noch stärker abweichend, und zwar wie folgt: "Moths released during daylight hours do not behave normally, and if prompted to fly, they will settle quickly on just about the first thing to encounter. In my view, the greatest weakness of Kettlewell’s mark-release-recapture experiments is that he released his moths during daylight hours" (Grant 1999, p. 5).

Weiter Majerus, p. 125:

"…observations of peppered moths being taken from natural resting positions are still lacking…"

Und der Zusammenhang (Thema "predation"):

Although observations of peppered moths being taken from natural resting positions are still lacking and are urgently needed, it is highly probable that predation levels are significant.

Majerus pp. 129/130:

"

...moths were put out for predation in unnatural positions, exposed and low down on tree trunks, rather than in their probable natural resting positions under branches or twigs in the canopy.Zusammenhang:

We suggested that the poorness of fit of Bishop’s simulation to observed frequencies may result from quantitative errors in the relative fitnesses obtained, because moths were put out for predation in unnatural positions, exposed and low down on tree trunks, rather than in their probable natural resting positions under branches or twigs in the canopy.

Majerus, p. 132:

"

While this is reasonable for the green brindled crescent and Diurnea fagella which both rest on tree trunks, it is not reasonable for the peppered moth, which rests elsewhere."Zusammenhang:

First, unfortunately, Steward assessed relative crypsis of moths by comparing them with tree trunks. While this is reasonable for the green brindled crescent and Diurnea fagella which both rest on tree trunks, it is not reasonable for the peppered moth, which rests elsewhere. (Zur Frage des weiteren Zusammenhangs vgl. man die Originalarbeit.)

Zur Richtigkeit der oben zitierten Aussagen gibt es sogar einen selektionstheoretischen Hinweis. Majerus berichtet p. 130:

"Carys Jones…found that those [dead] moths under lateral branches were about half as likely to be preyed upon than those on the trunks."

Und wieder der genaue Zusammenhang:

The lower predation level for moths below branch trunk joints compare with those in exposed positions on trunks was endorsed by Carys Jones (1993), who conducted experiments placing dead moths of two species (peppered moth and brindled beauty) on trunks, or under horizontal branches, in Madingley Wood, Cambridge, at low density (two per acre). She found that those moths under lateral branches were about half as likely to be preyed upon than those on the trunks.

Und wenn diese Beobachtung im Ansatz auch für die lebenden Birkenspanner gilt (das war ja eine der Grundvoraussetzungen in zahlreichen Experimenten), dann gab es schon eine Jahrmillionen währende Selektion gegen den Aufenthalt "in exposed positions on tree trunks."

Soweit erst einmal Majerus. Seine Aussagen sind nach meinem Verständnis vollkommen eindeutig:

"… peppered moths do not naturally rest in exposed positions on tree trunks …", "… peppered moths do not habitually rest in exposed positions on tree trunks …", "… peppered moths generally rest in unexposed positions …", "Mikkola … concluded that in nature this species probably rest on the underside of horizontal branches in the canopy …", "Liebert and Brakefield … obtained similar results. Most of the moths rested under, or on the side of, horizontal branchlets in the tree canopy …", "… the view that peppered moths do not always, or even usually, rest in exposed positions in tree trunks is not original. Kettlewell (1958b) himself was aware [of this] ...", "… observations of peppered moths being taken from natural resting positions are still lacking …", ".. .moths ... in unnatural positions, exposed and low down on tree trunks, rather than in their probable natural resting positions under branches or twigs in the canopy ...", "... the green brindled crescent and Diurnea fagella which both rest on tree trunks, ... [but] ... the peppered moth ... rests elsewhere."

c) Die Zusammenfassung der Biston-Problematik nach Jonathan Wells

Jonathan Wells, der im Gegensatz zu den oben zitieren Biologen von der Richtigkeit der ID-Theorie überzeugt ist, hat in voller Übereinstimmung mit den oben zitierten biologischen Tatsachen sowie den Aussagen der soeben aufgeführten Vertreter der Synthetischen Evolutionstheorie die Problematik des Birkenspanners für die Synthetische Evolutionstheorie (2000, pp. 149/150) wie folgt zusammengefasst:

Since 1980...evidence has accumulated showing that peppered moths do not normally rest on tree trunks. Finnish zoologist Kauri Mikkola reported an experiment in 1984 in which he used caged moths to assess normal resting places. Mikkola observed that "the normal resting place of the Peppered Moth is beneath small, more or less horizontal branches (but not on narrow twigs) probably high up in the canopies, and the species probably only exceptionally rests on three trunks." He noted that "night-active moths, released in an illumination bright enough for the human eye may well choose their resting sites as soon as possible and most probably atypically."

Although Mikkola used caged moths, data on wild moths supported his conclusion. In twenty-five years of field work, Cyril Clarke and his colleagues found only one peppered moth naturally perched on a tree trunk; they concluded that they knew primarily "where the moths do not spend the day." When Rory Howlett and Michael Majerus studied the natural resting sites of peppered moths in various parts in England, they found that Mikkola’s observations on caged moths were valid for wild moths as well. "It seems certain that most B. betularia rest where they are hidden," they concluded, and that "exposed areas of tree trunks are not an important resting site for any form of B. betularia." In a separate study reported in 1987, British biologists Tony Liebert and Paul Brakefield confirmed Mikkola’s observations that "the species rests predominantly on branches…. Many moths will rest underneath, or on the side of, narrow branches in the canopy."

In a 1998 book on industrial melanism, Michael Majerus defended the classical story but criticized the "artificiality" of much of the work on peppered moths, noting that in most predation experiments they were "positioned on vertical tree trunks, despite the fact that they rarely chose such surfaces to rest upon in the wild."

Drei Punkte zur Ergänzung der Aussagen nach Majerus lassen sich auf Grund der Darstellung von Wells hier vielleicht noch besonders hervorheben:

Mikkola observed that [Direktzitat] "the normal resting place of the Peppered Moth is beneath small, more or less horizontal branches"

Tony Liebert and Paul Brakefield…confirmed that [Direktzitat] "the species rests predominantly on branches…. Many moths will rest underneath, or on the side of, narrow branches in the canopy."

...Majerus..criticised...that in most predation experiments they were "positioned on vertical tree trunks, despite the fact that they rarely chose such surfaces to rest upon in the wild."

Zum Zusammenhang der Zitate vgl. die Ausführungen von Wells oben. (Siehe auch http://www.discovery.org/viewDB/index.php3?command=view&id=1147&program=CRSC Moth-eaten Statistics: A Reply to Kenneth R. Miller by Jonathan Wells und http://www.iconsofevolution.com/embedJonsArticles.php3?id=590 bzw. http://www.arn.org/docs/wells/jw_pepmoth.htm Second Thoughts about Peppered Moths: This classical story of evolution by natural selection needs revising.

d) Ein paar Ergänzungen durch die Arbeit von Judith Hooper

Hooper berichtet im Detail, dass Bernard Kettlewell nach jahrelang anhaltenden schweren psychischen und körperlichen Krankheiten und deren zunehmenden Komplikationen am 11. Mai 1979 Selbstmord beging (p. 225/126):

"...his entry in The Dictionary of Scientific Biography states, ‘apparently from an accidental overdose of the painkiller he was using to relieve a back injury sustained during field work’. The overdose was not an accident. Bernard was a doctor and knew exactly how to commit suicide efficiently. Whether the precipitating factor was intractable back pain or dread of Alzheimer’s disease or general discouragement or all of the above, he did what he had always matter-of-factly told his friends he would do when all hope was lost. Someone who had seen him that day found him cheerful, even ebullient, and found it hard to believe that he could have taken his life by the end of the day. But his old friend Cyril Clarke said that Bernard’s mood swings were so extreme that it was highly possible for him to have been on top of the world one moment and suicidal the next.**

Diesen Punkt erwähne ich hier, weil Kauri Mikkola andeutet, dass er erleichtert war, seine Entdeckung, nämlich "his [Mikkola’s] awkward finding, confirmed experimentally, that peppered moths did not rest on tree trunks" nicht mit Kettlewell diskutiert hatte: "When he heard the news about Bernard’s suicide the next spring, ‚I was most happy that I did not argue with him about the resting background’ " (nach Hooper, p. 260). Andernfalls hätte er sich wohl Vorwürfe gemacht, zum Selbstmord Kettlewells durch die Infragestellung der Grundlagen der Selektionsdeutungen beigetragen zu haben. Doch Hooper zitiert mit Majerus ebenfalls den Punkt, den ich mit Kettlewell oben schon dokumentiert habe (p. 260):

In fact, Mikkola would have confirmed what Bernard [Kettlewell] had himself observed. ‘Bernard knew this perfectly well,’ Michael Majerus asserts. ‘There is an obscure paper by Kettlewell on microhabitats in which he says he’s often watched peppered moths take up their natural resting positions on the underside of lateral branches. He watched them doing this.’ When his laboratory experiments showed that moths pass the day on the underside of branches, not on trunks, Mikkola pointed out that the conclusions drawn from the predation experiments could not be trusted.

Auf der Seite 262 lenkt Hooper die Aufmerksamkeit des Lesers auf einen Beitrag in dem Wissenschaftsmagazin New Scientist, das schon 1987 den hier diskutierten Hauptpunkt deutlich herausgearbeitet hatte. Sie berichtet:

By the time a 1987 article entitled ‘Exploding the myth of the melanic moth’ appeared in the popular British science magazine New Scientist, the flaws in the case had multiplied. The author, Jeremy Cherfas, reported that ‘after 20 years of moth-hunting’ Rory Howlett and Michael Majerus of Cambridge had concluded that peppered moths generally rest in unexposed positions, in the shadow a few inches below a branch/trunk joint, on the underside of branches, or on twigs. There study echoed Mikkola’s findings from almost a decade earlier.

In fact, not only did the moth not rest on tree trunks – a finding corroborated a year later by Tony Liebert and Paul Brakefield in the Netherlands – but a second crucial assumption was crumbling. As Cherfas reported, Howlett and Majerus took precise measurements of reflectance and reported that the light-coloured moth had partially translucent wings, so that ‘in terms of the light reflected from them, they are more black than white’.

Auch die folgenden Punkte erscheinen mir für die Geschichte der hier behandelten Kernfrage (Wo befinden sich die Birkenspanner in aller Regel tagsüber bzw. tagsüber nicht?) aufschlussreich. Hooper berichtet p. 263:

Many studies revealed a gap between the predictions based on Kettlewell’s model and the observations, about which Jim Bishop and Laurence Cook wrote in 1975: ‘The discrepancy may indicate we are not correctly assessing the true nature of the resting sites of living moths when we are conducting experiments with dead ones. Alternatively, the assumption that natural selection is entirely due to selective predation by birds may be mistaken.’

If selective predation by birds were the sole factor affecting frequency the most cryptic phenotype should have taken over in the areas where it was favoured, but this has never happened. Reviewing 115 years of breeding data, comprising 12,569 offspring from 83 broods, E.R. Creed et al. reported that unknown physiological factors in the pre-adult stages made the carbonaria homozygotes considerably hardier than typicals, heterozygotes, or the intermediate insularia. They analysed two cases where the carbonaria frequency increased rapidly in fairly unpolluted areas almost as soon as it appeared. Clearly there was, in the words of J.S.Jones, ‘more to melanism than meets the eye’.

‘So much stuff has been published by British scientists since Kettlewell, and none is very conclusive’, is Sargent’s conclusion. ‘Everything came out so cleanly for Kettlewell – too cleanly – and no one has gotten anything cleaner than mud.’

Weiter zitiert Hooper nach Hinweis auf den normalen 24-Stunden-Tagesablauf der Birkenspanner ("Peppered moths fly at night and settle into their daytime resting places at dawn. Bernard released his moth in daylight because if he had released them at night they would have made a beeline for the light traps.") Kettlewells Aussage zu einem seiner Experimente wie folgt (p. 266):

‘I admit that under their own choice, many would have taken up position higher in the trees, [and] in so doing would have avoided concentrations such as I produced.’

…. Mikkola, for one, observed that this method doomed the moths to ‘atypical’ positions. ‘In my view,’ wrote Bruce Grant, of the College of William and Mary in Virginia, ‘the greatest weakness in Kettlewell’s mark-release-recapture experiments is that he released his moths during daylight hours…’

Sie fasst ihre Hauptaussage p. 265 wie folgt zusammen:

By the early 1990s, if not before, it was known to a small circle of scientists that what every textbook in the Darwinian universe said about industrial melanism was untrue.

e) Theodore D. Sargent

Ted Sargent kommentiert einige Fotos aus Bernard Kettlewells Buch The Evolution of Melanism nach Hooper (2002, p. 244) wie folgt:

These are pinned specimens. They are dead; they were pinned up and then taken down. Sometimes they take a live one and let it crawl around and then take a picture of it. But they're all fake; no one has found one on a tree trunk. Who's going to find a moth out there like this, let alone two demonstrating crypsis?

Vorsichtiger hätte Sargent etwa wie folgt formulieren können: "...hardly any one has found one on a tree trunk." Denn Majerus berichtet von insgesamt 6 Exemplaren an solchen Stellen in 34 Jahren Forschung (Details siehe unten). Dennoch erscheint mir der generelle Eindruck, den ein weiterer sehr erfahrener Wissenschaftler wie Sargent aus Jahrzehnten eigener Forschung gewonnen hat, von nicht zu unterschätzender Bedeutung für unsere Frage zu sein: Die Birkenspanner rasten normalerweise tagsüber nicht in exposed positions on tree trunks (und "...Ted is the most meticulous, careful researcher. When he gets interested in something - if it's rocks and minerals, or herbs, or melanism - he pursues it with tremendous intensity" - John Mooner zitiert nach Hooper, p. 301). Sargents Frage ("Who's going to find a moth out there like this, let alone two demonstrating crypsis?") möchte ich an meine Leser weitergeben. Ich halte es zumindest für äußerst wahrscheinlich, dass auch in jahrzehntelanger und intensivster Arbeit niemand two moth demonstrating crypsis in an exposed position on a tree trunk in the wild finden wird. (Im Übrigen sei noch angemerkt, dass Sargent mit dem Gedanken an "fake" an anderer Stelle wesentlich vorsichtiger umgegangen ist, aber auf diese Frage möchte ich hier nicht weiter zu sprechen kommen; - vgl. Hooper, p. 255.)

Einige (weitere) Kommentare von Sargent, Millar und Lambert zur Frage, wo sich die Birkenspanner tagsüber in aller Regel aufhalten, bzw. nicht aufhalten:

Ted Sargent et al. (1998, p. 305):

...it seems clear that individuals do not commonly rest on vertical tree trunks.

Und der Kontext (pp. 305/306):

The dearth [Mangel] of field observations of naturally resting B. betularia has always been puzzling. It was Mikkola (1979) who obtained the first experimental evidence that these moths tend to rest high in trees, mostly on the undersides of small horizontal branches. This finding has since been supported by Howlett and Majerus (1979) and Liebert and Brakefield (1987), although the latter contend that there is a more varied choice of resting positions than suggested by Mikkola (1979). Clarke et al. have rejected Mikkola's (1984) interpretation [allerdings nur hinsichtlich der camouflage durch Flechten; siehe das Zitat oben], remarking, "...we do not think that this type of protection occurs in our area, and all we have observed is where the moths do not spend the day." Despite this uncertainty as to where the moths rest, it seems clear that individuals do not commonly rest on vertical tree trunks. Consequently, the interpretation of many background choice experiments, in which this was a major assumption, is difficult.

Und dieselben Autoren bemerken zu unserer Frage ein paar Seiten weiter (p. 313):

...the normal resting sites of B. betularia remain uncertain but are almost certainly not the exposed tree trunks onto which the moths were originally released in this study.

Und wieder der Kontext dieser Aussage im Rahmen der Kommentare von Sargent et al. zu Kettlewells "Mark-Release-Recapture Studies" (p. 313):

First he released a number of marked individuals of the three morphs of B. betularia (typical,

carbonaria, and insularia) at a site in industrial Birmingham. Trapping over subsequent days revealed that the frequency of typicals recaptured

was reduced relative to carbonaria. A similar experiment was then conducted in unpolluted Dorset, and here the frequency of carbonaria recaptured was

reduced relative to typicals. The differences were significant in both cases, and so these results were consistent with the hypothesis of selective predation

on the more conspicuous morph. Indeed, these experiments still provide the primary evidence for the "classical" industrial melanism story.

This study, however, was beset with many problems, and Sermonti and Catastini (1984) have concluded that

"...Kettlewell's experiments do not prove in any acceptable way, according to the current scientific standard, the process he maintains to

have experimentally demonstrated."

We have already discussed some of the problems that could have affected the results of this study.

For example, the normal resting sites of

B. betularia remain uncertain but are almost certainly not the exposed tree trunks onto which the moths were originally released in this study.

Sermonti and Catastini (1984) and Mikkola (1984) have pointed out that this problem would have been most significant on the first day of

each study (Birmingham and Dorset) because the moths, when released during daylight, presumably settled quickly, and quite likely on sites that they

would not have chosen under normal, free-flying conditions (presumably, moths normally select their daytime resting sites around dawn). In fact,

when Mikkola (1984) reanalyzed Kettlewell's results, after removing the first day's recapture figures, he found that the remaining data were insufficient

to permit statistical analyses of differences among the morphs. Further, if he combined typicals and insularia for the Birmingham data

(as Kettlewell did), then there was no significant difference between the recapture rates of these morphs combined and

that of carbonaria.

f) Kauri Mikkola

Auf Kauri Mikkolas Aussagen haben oben schon zahlreiche Biologen Bezug genommen. Sehen wir uns daher aus seinen Originalarbeiten einige Punkte näher an. Er bemerkt unter anderem (1979, p.81):

As pointed out by Boardman et al. (1974), the use of observations from nature may be a pitfall: it is possible that moths

easily perceived by an observer are those which have happened to settle in an atypical resting site. This may lead to wrong generalizations

about the behaviour of the species. If such unusual resting sites are used in predation experiments, the preditors, usually birds, may

notice the moths more frequently than those in typical resting places or, alternatively, the selection of various colour forms may be different

from that found in nature.

(1979, p. 86:) Of about 100 lepidopterists present at a monthly meeting of the Finnish Lepidopterological Society, nobody

had ever found the

species in day-rest on tree trunks. Similarly, lepidopterists in Germany have wondered why the species is hardly ever found on trunks,

if these constitute the main resting place of the species (G. Ebert and S. Wagner, oral comm.). The scarcity of observations is understandable

if the majority of the moths rest in the day-time high up on trees, mostly small horizontal branches.

[Und weiter unten fährt Mikkola fort:] Branches provide a more variable background (and show more contrasts) than trunks; overall branch

surface area is much larger and usually it seems to be darker. The underside of a horizontal branch, where the moths tend to rest, is in shadow,

it may often be wet (cf. Lees & Creed 1975) and smoke particles in rainwater may accumulate on it. Therefore, the relative cryptic characteristics

of the colour forms may be different from those found by placing dead moths on the trunks.

(1979, p. 87:) …as Bishop (1972) has noted, different birds may hunt at different heights in the trees. [Dann folgt Lob auf

Kettlewells Arbeiten “provided

that the releasing procedure is correct”.]

(1984, p. 409): In nature, Biston betularia [Mikkola schreibt regelmäßig "betularius”, warum habe

ich noch nicht herausgefunden]

probably rests high in the canopies, on the under surfaces of horizontal branches. The visual selection acting on the morphs is expected to be

less intensive than that measured on tree trunks.

(1984, p. 416:)

It seems clear that the normal resting place of the Peppered Moth is beneath small, more or less horizontal branches (but not on narrow twigs),

probably high up in the canopies, and the species probably only exceptionally rests on tree trunks.

…The tree canopy contains quite different resting sites from the trunks on which the species was believed to rest. The surface area

must be considerably larger and the environment is more variegated, with contrasts between the bright background and the branches

and between the light upper surfaces and shaded under surfaces of the branches. In short: among the twigs the protective colours are

expected to be of less significance than on the trunks.

g) Schließlich ein Wort von Bruce S. Grant

Vorweg sei erwähnt, dass B.S. Grant sicher einer der entschlossensten Verteidiger der Synthetischen Evolutionstheorie und des Biston-Beispiels ist (vgl. oben "Sour Grapes of Wrath"). Grant schreibt 1999, p. 4:

In truth, we still don’t know the natural hiding places of the peppered moth.

Zusammenhang:

Majerus has discovered 47 peppered moths at rest by day in the wild. (The large samples of peppered moths used to calculate melanic frequencies in local populations come from operating light traps and assembling [pheromone] traps at night. It's rare, indeed, to find a peppered moth away from a trap by day even where the species is abundant.) Majerus separates into categories the position on trees where the moths were located (trunk, trunk/branch joint, branches). While the trunk/branch joint was the most common site, his data indicate that the moths do not all rest in the same place. As Clarke et al. (1994) put it: "Moths habitually resting in only one place will be habitually sought there." Mikkola (1984), based on his observations of moths kept in captivity, suggested that peppered moths hide by day on the underside of branches in the canopy. Grant and Howlett (1988) showed that captive moths move to whatever end of their holding pen light enters (if the light enters from the bottom of the pen, the moths will sit on the floor). Perhaps Mikkola’s conclusion is correct, but perhaps his evidence is an artifact of his apparatus. In truth, we still don’t know the natural hiding places of peppered moths.

Wie oben jedoch schon betont, würden wir "the natural hiding places of the peppered moth" längst kennen, wenn sich die meisten Birkenspanner tagsüber – wie nach gängigen Lehrbuchdarstellungen zu erwarten – "in unexposed positions on tree trunks" aufhalten würden. Denn wir hätten dort schon Tausende von Exemplaren allein in den letzten fünfzig Jahren gefunden!

Mit anderen Worten: Würden die Birkenspanner in aller Regel tagsüber "in exposed positions on tree trunks" Rast machen, dann wüßte man es!

5. Wiederholung der Hauptergebnisse zur Frage, wo sich sich Biston betularia in aller Regel tagsüber bzw. tagsüber nicht befindet

"… peppered moths do not naturally rest in exposed positions on tree trunks …", "… peppered moths do not habitually rest in exposed positions on tree trunks …", "… peppered moths generally rest in unexposed positions …", "Mikkola … concluded that in nature this species probably rest on the underside of horizontal branches in the canopy …", "Liebert and Brakefield … obtained similar results. Most of the moths rested under, or on the side of, horizontal branchlets in the tree canopy …", "… the view that peppered moths do not always, or even usually, rest in exposed positions in tree trunks is not original. Kettlewell (1958b) himself was aware [of this] ...", "… observations of peppered moths being taken from natural resting positions are still lacking …", ".. .moths ... in unnatural positions, exposed and low down on tree trunks, rather than in their probable natural resting positions under branches or twigs in the canopy ...", "... the green brindled crescent and Diurnea fagella which both rest on tree trunks, ... [but] ... the peppered moth ... rests elsewhere."

Mikkola observed that [Direktzitat] "the normal resting place of the Peppered Moth is beneath small, more or less horizontal branches…"

Tony Liebert and Paul Brakefield…confirmed that [Direktzitat] "the species rests predominantly on branches… Many moths will rest underneath, or on the side of, narrow branches in the canopy."

"...Rory Howlett and Michael Majerus of Cambridge had concluded that peppered moths generally rest in unexposed positions, in the shadow a few inches below a branch/trunk joint, on the underside of branches, or on twigs. There study echoed Mikkola’s findings from almost a decade earlier."

Sargent: "...it seems clear that individuals do not commonly rest on vertical tree trunks."

Mikkola: "Of about 100 lepidopterists present at a monthly meeting of the Finnish Lepidopterological Society, nobody had ever found the species in day-rest on tree trunks. Similarly, lepidopterists in Germany have wondered why the species is hardly ever found on trunks, if these constitute the main resting place of the species..."

Grant: In truth, we still don’t know the natural hiding places of the peppered moth. – Sie befinden sich somit tagsüber normalerweise nicht "in exposed postions on tree trunks", sonst wüssten wir es.

Weitere Punkte siehe oben.

6. Die Verneinung dieser Sachkritik

Da nun meines Wissen keiner der hier zitierten Evolutionsbiologen seine Aussagen zur Frage, wo sich Biston in aller Regel tagsüber aufhält bzw. nicht aufhält, widerrufen hat, - wie ist es dann möglich, dass andere Vertreter der Synthetischen Evolutionstheorie diese Antworten für völlig unhaltbar betrachten, so als hätten die oben zitierten Forscher vielmehr folgende Phänomene in völliger Übereinstimmung mit den bisherigen Lehrbuchdarstellungen festgestellt? Die oben dokumentierten Aussagen müssten im Falle der Richtigkeit der Gegenkritik wie folgt korrigiert werden:

"… peppered moths do naturally rest in exposed positions on tree trunks …", "… peppered moths do habitually rest in exposed positions on tree trunks …", "… peppered moths generally rest in exposed positions …", "Mikkola … concluded that in nature this species definitely rest in exposed positions on tree trunks …", "Liebert and Brakefield … obtained similar results. Most of the moths rested in exposed positions on tree trunks ...", "… the view that peppered moths do always, or at least usually, rest in exposed positions in tree trunks was already detected by Kettlewell (1958b). So he himself was fully aware [of this] ...", "… there is an abundance of observations of peppered moths being taken from natural resting positions …", "... moths ... in their natural positions, exposed and low down on tree trunks, rather than in their improbable resting positions under branches or twigs in the canopy ...", "... the green brindled crescent and Diurnea fagella as well as the peppered moth ... all rest on tree trunks."

Mikkola observed that [Direktzitat] "the normal resting place of the Peppered Moth is in exposed positions on tree trunks …"

Tony Liebert and Paul Brakefield…confirmed that [Direktzitat] "the species rests predominantly in exposed positions on tree trunks …. Hardly any moths will rest underneath, or on the side of, narrow branches in the canopy."

"...Rory Howlett and Michael Majerus of Cambridge had concluded that peppered moths generally rest in exposed positions, not in the shadow a few inches below a branch/trunk joint, on the underside of branches, or on twigs. Their study echoed Mikkola’s findings from almost a decade earlier."

"...it seems clear that individuals commonly rest on vertical tree trunks."

Mikkola: "Of about 100 lepidopterists present at a monthly meeting of the Finnish Lepidopterological Society, everybody had found the species in day-rest on tree trunks. Similarly, lepidopterists in Germany have often found peppered moths in exposed postions on trunks, because the latter constitute the main resting place of the species..."

"In fact, we do know the natural hiding places of the peppered moth."

Wie oben schon erwähnt: Wenn diese "korrigierten" Aussagen tatsächlich den bisherigen Beobachtungen und Forschungsergebnissen entsprechen würden, würde ich sie akzeptieren.

Gibt es aber irgendeine faktische Grundlage für solche Korrekturvorschläge? Sehen wir uns zu dieser Frage R. Millers Interpretation von zwei Tabellen aus der Arbeit von Majerus näher an.

7. Die Fehlinterpretation zweier Tabellen aus Michael E. N. Majerus durch Kenneth R. Miller

Mit dem Link auf J. Wells zu den "Moth-eaten Statistics" könnte ich mich (in Anlehnung an die Antwort durch Literaturhinweise von Herrn E.F.) eigentlich begnügen, doch möchte ich die zur Debatte stehenden Tabellen und einige Details dazu direkt aufführen und diskutieren. Denn die Fehlinterpretation von Kenneth R. Miller empfinde ich als symptomatisch für die Vorgehensweise führender Neodarwinisten und Lehrbuchverfasser bei der vorliegenden und ähnlichen Fragen.

(Den Streit zwischen Miller und Wells zur Frage, ob es sich bei den Lehrbuchdarstellungen um "fraud" handelt oder nicht, möchte ich an dieser Stelle jedoch ausdrücklich ausklammern – es geht uns hier weiter um den Kernpunkt, wo sich die Birkenspanner in aller Regel tagsüber aufhalten und wo nicht).

M. Majerus hat über seinen oben schon ausführlich referierten und zitierten Text zur Frage nach den resting positions of peppered moths hinaus zwei Tabellen (Table 6.1 und Table 6.2) auf der Seite 123 seines Werkes Melanism – Evolution in Action (1998) aufgeführt, die im Folgenden wiedergegeben seien:

Table 6.1 The resting positions of peppered moths found in the wild between 1964 and 1998 (Adapted, with additional data, from Howlett and Majerus 1987.)

| typica | insularia | carbonaria | |

| Exposed trunk | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Unexposed trunk | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Trunk/branch joint | 10 | 4 | 6 |

| Branches | 5 | 3 | 7 |

Table 6.2 Resting positions of peppered moths found in the vicinity of mercury vapour moth traps at various locations, between 1965 and 1996. (Adapted, with additional data, from Howlett and Majerus 1987.)

| typica | insularia | carbonaria | |

| Exposed trunk | 25 | 7 | 16 |

| Unexposed trunk | 10 | 6 | 6 |

| Trunk/branch joint | 33 | 10 | 23 |

| Branches | 9 | 4 | 7 |

| Foliage | 9 | 5 | 8 |

| Man-made surfaces | 13 | 5 | 7 |

Kenneth R. Miller fasst die beiden Tabellen in Summaries wie folgt zusammen (

vgl http://www.millerandlevine.com/km/evol/wells-april-2002.html).1) Zu Tabelle 6.1: Summary: 32 of 47 moths (68%) were found on tree trunks

2) Zu Tabelle 6.2: Summary: 136 of 203 moths (67%) were found on tree trunks

Und Miller schreibt unter anderem:

Wells presents a series of quotes from the literature to support his contention, made in "Icons," that peppered moths don't rest on tree trunks, a claim I rebutted in the debate. Like many opponents of evolution, he argues from quotation rather than from data. At the debate, I presented actual data on the positions in which moths have been observed in the wild, and guess what? Although the literature is clear that adequate studies have not yet been done to pinpoint the places where these moths generally rest in the wild, observations done to date show that most moths have, indeed, been found on tree trunks.

- Worauf die Daten der oben zitierten Tabellen jeweils zusammengefasst aufgeführt werden. Daran anschließend bemerkt Miller:

What these uncontested data mean, of course, is that Wells' flat statement that the moths don't rest on tree trunks is wrong, no matter how many quotations he musters in support of his view. Quotations are not data. The data show that moths are indeed found on tree trunks, and that's what I said at the debate.

Zunächst ein Wort zu Millers Punkt: "Like many opponents of evolution, he argues from quotation rather than from data."....."Quotations are not data." – Als könnten Zitate nicht auf Daten beruhen oder als würden Zitate grundsätzlich keine Daten enthalten! - Aber die Tabellen selbst sind natürlich auch Zitate, nämlich direkte Datenzitate. Tatsache ist, dass die Aussagen von Zitaten auf umfangreichen Datenmengen beruhen können, bzw. solche häufig zusammenfassen. Beispiel:

Die oben wiedergegebene Aussage von Sir Cyril Clarke (‘All we have observed is where moths do not spend the day. In 25 years we have found only two betularia on the tree trunks or walls adjacent to our traps (one on an appropriate background and one not), and none elsewhere’) ist auf dem Hintergrund ihrer Arbeit zu sehen (zur Erinnerung): "From 1959 until the late 1990s, the Clarkes never missed a summer of daily trapping and ended up with data spanning more than three decades, more than 18,000 specimens in all, that documented in full the historic demise of the melanic peppered moth.

Das Clarke-Zitat gibt also nicht etwa irgendeine unbegründete Meinung zur Frage des Aufenthalts von Biston von jemandem wieder, der nicht weiß, wovon er spricht, sondern beruht auf dem Hintergrund von genauen Auszählungen des Gesamtmaterials (jedoch ohne genaue Ortsangaben der Rastplätze, da schwer im Blätterdach feststellbar) im Verhältnis zu den auf tree trunks gefundenen Exemplaren (relativ leicht feststellbar) aus den langjährigen Erfahrungen eines der besten Kenner der Materie.

8. Widerspricht sich Majerus?

Und wenn Majerus u.a. feststellt (siehe Zusammenhänge oben):

"… peppered moths do not naturally rest in exposed positions on tree trunks …", "… peppered moths do not habitually rest in exposed positions on tree trunks …", "… peppered moths generally rest in unexposed positions …", "Mikkola … concluded that in nature this species probably rest on the underside of horizontal branches in the canopy …", "Liebert and Brakefield … obtained similar results. Most of the moths rested under, or on the side of, horizontal branchlets in the tree canopy …", "… the view that peppered moths do not always, or even usually, rest in exposed positions in tree trunks is not original. Kettlewell (1958b) himself was aware [of this] ...", "… observations of peppered moths being taken from natural resting positions are still lacking …", "... moths ... in unnatural positions, exposed and low down on tree trunks, rather than in their probable natural resting positions under branches or twigs in the canopy ...", "... the green brindled crescent and Diurnea fagella which both rest on tree trunks, ... [but] ... the peppered moth ... rests elsewhere."

- Dann beruhen diese Aussagen natürlich ebenfalls auf umfangreichen Datenmengen.

Wie aber passen nun diese auf jahrelangen Datensammlungen beruhenden zusammenfassenden Aussagen von Majerus mit den Daten aus seinen Tabellen 6.1 und 6.2 zusammen?

Wenn Majerus tatsächlich mit Miller generell sagen möchte, dass sich 68%, bzw. 67% der Birkenspanner tagsüber ‘auf Baumstämmen’ befinden, dann würden seine soeben zitierten zusammenfassenden Datenaussagen im Vergleich zu seinen Tabellenaussagen sicher zu den eklatantesten Widersprüchen gehören, die vielleicht jemals in der Wissenschaftgeschichte hervorgebracht worden wären.

Des Rätsels Lösung ist jedoch einfach: Die Tabellendaten müssen selbstverständlich auf dem Hintergrund von den Tausenden von Biston-Exemplaren gesehen werden, die zum einen von Majerus und Clarke und anderen Autoren untersucht worden sind und die zum anderen als Gesamtzahl einer Biston-Population in einem bestimmten gründlich durchforschten geographischen Areal überhaupt existieren.

Wenn man von vornherein weiß, dass man die Biston-Exemplare im Blätterdach eines Waldes schwer nachweisen kann (

selbst wenn man die Canopy-Schicht Ast für Ast "freischwebend" absuchen könnte, dann wäre das immer noch eine ungeheuer mühselige Aufgabe, denn auch nur hundert Meter im Quadrat hieße zehntausend Quadratmeter Blätterdach nach Biston abzusuchen, vielleicht etwas weniger, wenn man sich auf die kleinen Äste konzentriert (aber "at low density (two per acre)" [1 acre = 4 046,8 Quadratmeter]? – dagegen erscheint jedenfalls die Suche nach Exemplaren "in exposed positions on tree trunks" relativ einfach), dann kann man die Frage, wo sich die Birkenspanner in aller Regel tagsüber aufhalten bzw. wo nicht, also keineswegs mit den absoluten, aber nur einen winzigen Bruchteil der Gesamtpopulation der Birkenspanner ausmachenden Tabellenzahlen in dem Sinne beantworten, dass man die sich daraus ergebenen falschen Relationen (denn die einen findet man kaum, die anderen aber relativ leicht) einfach verabsolutiert.Majerus selbst hat dazu auf Folgendes hingewiesen (siehe auch oben): "They [Howlett and Majerus] also note that their data are bound to be biased towards the lower parts of trees, as these are most easily searched." Und 1987, p. 40, haben die Howlett und Majerus zu den beiden 'Vorläufer-Tabellen' mit den bis dahin bekannten Daten Folgendes angemerkt (Numerierung von mir):

All these data are obviously observer-biased. The majority of the records were obtained while looking for Lepidoptera in general. B. betularia was not being sought specifically. [1.] Tree trunks were searched very much more often than other potential resting surfaces. [2.] Moths resting in exposed positions on trunks would obviously be more easily seen than those hidden behind foliage or deep in bark crevices. [3.] Only the lower areas of the trunks could be searched, so the majority of records apply to the bottom 2 metres of the trunk, and [4.] there were no sightings above 5 m. [5.] The number of branch joints low down on the trunk is limited as is the number of branches which can be searched. [6.] If most moths rest high up in the canopy or on foliate twigs, these would have been missed. [7.] The bias will be increased if the forms rest in situations where they are best camouflaged, for then an observer will obviously see those individuals in abnormal positions most easily.

(Bold und kursiv auch hier wieder von mir.) In den folgenden Jahren dürfte man auch 'specifically' nach Biston betularia Ausschau gehalten haben. (Wer forscht einmal genau nach oder noch besser, sucht selbst nach Birkenspannern in exposed positions on tree trunks? Dabei ist zu berücksichtigen, dass die Birkenspanner keineswegs nur oder auch nur vor allem auf Birken vorkommen: von den 25 Biston betularia-Exemplaren, die Majerus bis 1985 gefunden (und 1987 publiziert) hatte, berichtet er Folgendes (p.39): "Moths were found on a range of trees; oak (13); birch (5); apple (2); and hawthorn, poplar, elm, horse chestnut and Douglas fir (one each)." Es sei hervorgehoben, dass von diesen 25 Exemplaren nur 4 der Gruppe "exposed trunk" zugeordnet und überdies nur 2 bis 1998 zu dieser Kategorie addiert werden konnten). Die Daten der Tabellen sind jedenfalls in den entscheidenden sieben Punkten "observer-biased" - wobei der 7. Punkt kaum auf die ersten 2 m der Baumstämme zutrifft (diesen Teil kann man ja ohne größere Schwierigkeiten ganz genau inspizieren) - dafür aber fast vollständig auf Höhen über 5 m. Und ich möchte an dieser Stelle an das oben zitierte Wort Lord Actons erinnern: "The worst use of theory is to make men insensible to fact" – und Fakt ist, dass die Daten "observer-biased" und insbesondere "biased toward the lower part of the trees" sind!

Howlett und Majerus beurteilen die Frage nach den relativen Frequenzen weiter wie folgt (1987, p. 40):

Despite these inbuilt biases a number of conclusions can be drawn from these data. Of the moths found when collecting in the wild the majority were in relatively unexposed positions of one sort or another. When the bias in being able to see exposed individuals is taken into account it seems certain that most B. betularia rest where they are hidden. We conclude, from the data and in a consideration of the way collecting was carried out that B. betularia habitually utilizes three main resting situations: (a) tree trunks within a very short distance of a branch/trunk join, and always below so that the moth is in shadow; (b) on branches, and again probably on the underside; (c) on foliate twigs. The observer bias makes an appraisal of the relative importance of these sites impossible. We are, however, convinced that exposed areas of tree trunks are not an important resting site for any form of B. betularia.

Das heißt also, wir können die Tabellenwerte nicht verabsolutieren und von den Zahlen etwa auf die "relative importance of these sites" schließen, wie die Autoren selbst betonen indem sie schlussfolgern: "The observer bias makes an appraisal of the relative importance of these sites impossible." Dennoch haben die Verfasser hier einen entscheidenden Punkt in ihren Überlegungen nicht mit einbezogen: Auf dem Hintergrund der Gesamtpopulationen von Zehntausenden von B. betularia-Exemplaren, die sich ja tagsüber "irgendwo" befinden müssen, sind in 34 Jahren von Majerus in the wild nur 6 Individuen in exposed positions on tree trunks gefunden worden, also gerade dort, wo sie am leichtesten von allen oben diskutierten Möglichkeiten zu entdecken waren. Es befinden sich also nach den mir bisher zugänglichen Daten etwa (oder vielleicht auch mehr als) 99,9 % aller Birkenspanner tagsüber nicht in exposed positions on tree trunks. Bei den von Miller sowie Tamzek (Matzke) und Grant (siehe unten) angenommenen Prozentsätzen hingegen hätte man B. betularia-Individuen dort in großen Zahlen schon gefunden (selbst wenn man bis heute nur nach den Lepidoptera im Allgemeinen Ausschau gehalten hätte).

9. (a) Wells Kommentar zu Millers Deutung der Tabellen

Jonathan Wells hat die Gesamtproblematik der Auffassung Millers wie folgt zusammengefasst (Moth-eaten statistics. A reply to Kenneth R. Miller - mit einigen Anmerkungen zur Ergänzung von mir):